Countering Terrorism

Definitional dimensions

For at least several decades, States have sought to prevent acts of terrorism and punish those who commit, attempt to commit, or otherwise support acts of terrorism. In doing so, States have adopted a variety of conceptual notions concerning what qualifies as an act of terrorism and other proscribed terrorism-related conduct, including “supporting” acts of terrorism. In the absence of a general international legal definition, in several treaties States have enshrined a range of notions of prohibited terrorism-related conduct, from bombing a government facility to providing financial support to a designated terrorist group. In practice, some conduct that is proscribed under definitions of terrorism or support-to-terrorism activities in international legal instruments or national legal systems is undertaken in connection with an armed conflict. Yet many — indeed, perhaps most — manifestations of prohibited terrorism-related conduct are not connected with an armed conflict.

Diverse measures

Under the rubric of countering terrorism, States have taken an increasingly broad and diverse array of actions at the global, regional, and national levels. The expansion of the type and scale of measures taken and the actors involved in efforts to counter terrorism may be seen as a recognition by States that preventing, suppressing, and punishing terrorism-related activities constitutes a significant policy objective. The measures are typically aimed at one or more of the following purposes: condemning the means or methods involved in terrorist conduct; preventing or deterring people from joining or otherwise supporting entities involved in terrorist conduct; depriving entities involved in terrorist conduct of the means to engage in that conduct; suppressing or intercepting terrorism-related conduct that may be in progress; and prosecuting and punishing attempted or completed acts of terrorism. Counterterrorism measures may be of a political, legal, economic, social, cultural, intelligence, or other nature. In terms of their material scope, counterterrorism measures may be conceptualized as encompassing a range of activities, potentially including such steps as: conducting military operations against terrorist groups in an armed conflict; instituting criminal, civil, or administrative proceedings against terrorists and their supporters; preventing the financing of terrorism; denying “safe haven” to terrorists and their supporters; and preventing the cross-border movement of terrorists.

Preconditions

Several preconditions arguably must exist to counter terrorism comprehensively. For example, as a starting point, what kinds and forms of conduct are of a terrorist nature or character arguably must be sufficiently well specified. Counterterrorism actors need to possess the knowledge, training, means, and facilities necessary to prevent, suppress, and punish terrorism-related conduct. Further, counterterrorism measures must pass legal muster, including by being grounded in a legal basis and being taken in a manner consistent with applicable international and national laws.

Legal Basics

How does international law regulate terrorism?

At the international level, there is no single, comprehensive body of counterterrorism laws. States have developed a collection of treaties to pursue specific anti-terrorism objectives, such as suppressing the financing of terrorism and terrorist bombings. In addition to treaties open to global participation, States have also developed numerous regional instruments. However, despite decades-long efforts, States have yet to conclude a Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism. The extent to which customary international law governs aspects of efforts to counter terrorism, including whether a definition of international terrorism may be ascertained under customary international law, is subject to ongoing debate and legal development

What is the role of the Security Council?

In recent decades, the Security Council has assumed an increasingly prominent role in countering terrorism, including by adopting decisions that U.N. Member States must accept and carry out under the U.N. Charter. Two sets of Security Council acts may be relevant.

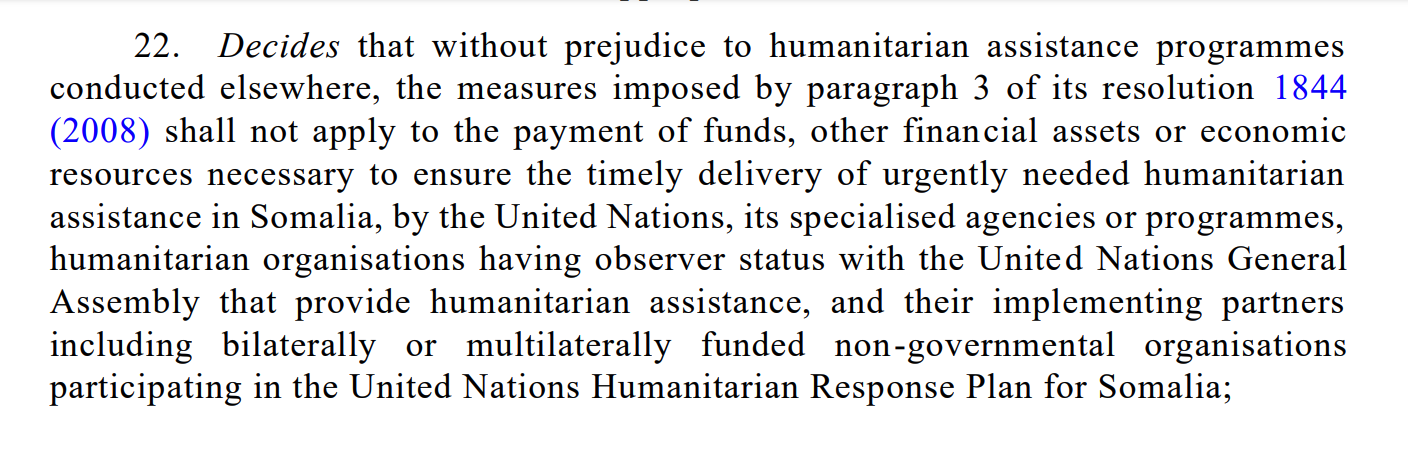

First, the Security Council’s acts under the Resolution 1267 (1999), Resolution 1989 (2011), and Resolution 2253 (2015) line of resolutions entail rights and obligations related to the imposition of sanctions measures — namely, an assets freeze, a travel ban, and an arms embargo — currently against the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida, and associated individuals, groups, undertakings, and entities. Medical activities are listed as part of the designation criteria for two people and two entities subject to those sanctions. Further, at least in theory, the imposition of the assets freeze and travel ban in relation to certain persons and entities subject to the “1267/1989/2253 ” sanctions may impede or prevent humanitarian and medical activities.

Second, the Council’s acts under the Resolution 1373 (2001) line of resolutions entail rights and obligations concerning an array of measures to counter terrorism, including with respect to preventing the financing of terrorist acts and ensuring that any person who participates in supporting terrorist acts is brought to justice. As part of that set of resolutions, the Security Council has decided that all States shall (among other actions) criminalize certain conduct related to “terrorist acts” and ensure that, in addition to any other measures against them, certain terrorist acts — including “supporting terrorist acts” — are established as serious criminal offenses in domestic laws and regulations and that the punishment duly reflects the seriousness of those terrorist acts. Notably, the Security Council has not expressly defined what constitutes “terrorist acts” nor what constitutes “supporting” such acts in respect of this line of resolutions.

How do national legal systems counter terrorism?

National-level counterterrorism measures may originate in international law and policy (for example, as part of the State’s efforts to carry out a Security Council decision), in domestic law and policy, or in a combination thereof. In terms of the actors involved, a State’s national-level counterterrorism measures may be said to include the conduct of any agent of the State or State organ — whether it exercises a legislative, executive, judicial, or other function — with an object of countering terrorism. Such conduct also may include any other national-level counterterrorism measures attributable to the State, for example those measures taken by a group of persons (such as a private security contractor) who in fact act on the instructions of, or under the direction or control of, the State in carrying out a counterterrorism measure.

National-level counterterrorism measures must be devised and implemented consistent with applicable international and national laws. For example, counterterrorism measures taken by a State in relation to an armed conflict need to be consistent at least with applicable IHL. Other fields of international law — including international human rights law — as well as constitutional provisions, domestic legislation, executive instruments, and judicially mandated parameters may also be applicable in respect of national-level counterterrorism measures.

What are humanitarian “carve-outs”?

Some counterterrorism measures are designed and applied in a manner that implicitly or expressly “carves out” a particular safeguard, such as a limited exception or exemption, for certain humanitarian and medical activities or actors. However, most counterterrorism measures do not include such safeguards.

Where they do exist, such safeguards typically fall into one of two categories. One category comprises “bad-actor carve-outs” meant to ensure that people falling under a terrorist characterization or designation are not deprived of humanitarian or medical services. The second is “humanitarian-actor carve-outs” meant to ensure that the people, means, and facilities involved in humanitarian and medical activities are not subject to a particular counterterrorism measure. Where they exist, such safeguards for humanitarian and medical actors are typically limited along one or more of the following axes:

In terms of their material scope — that is, with respect to the specific kinds of humanitarian and medical activities that are carved out (such as safeguards that cover only relief activities but not also protection activities);

In terms of their personal scope — that is, with respect to the specific categories of humanitarian and medical actors whose activities are carved out (such as safeguards that cover only certain international agencies or organizations but not also local organizations or unaffiliated individuals);

In terms of their temporal scope — that is, with respect to the specific period(s) of time in which the covered humanitarian and medical activities are carved out (such as safeguards that will lapse after a year unless they are expressly renewed); and

In terms of their geographical scope — that is, with respect to the specific locations in which the covered humanitarian and medical activities are carved out (such as safeguards that cover humanitarian and medical activities only in government-controlled territory but not in territory under the de-facto control of a non-state party).

States, international bodies, private humanitarian and medical actors, and scholars are actively evaluating whether “carve out” safeguards are necessary or otherwise considered prudent and, if so, what form and content they can, should, or must entail. These actors are considering, among other aspects, whether carve-out safeguards are necessary or sufficient to ensure compliance with IHL rights and obligations pertaining to humanitarian and medical activities. Some of the safeguards pertain to specific counterterrorism measures — for example, terrorism-suppression sanctions at the international or national level. Others pertain to counterterrorism frameworks more generally — for example, in relation to a potential omnibus Security Council resolution.